Idaho State Professor’s Research Details “Microbial Conveyor Belt” Beneath Atlantic Ocean

October 13, 2022

The intersection of biology and geology is the subject of a new publication by an Idaho State University professor.

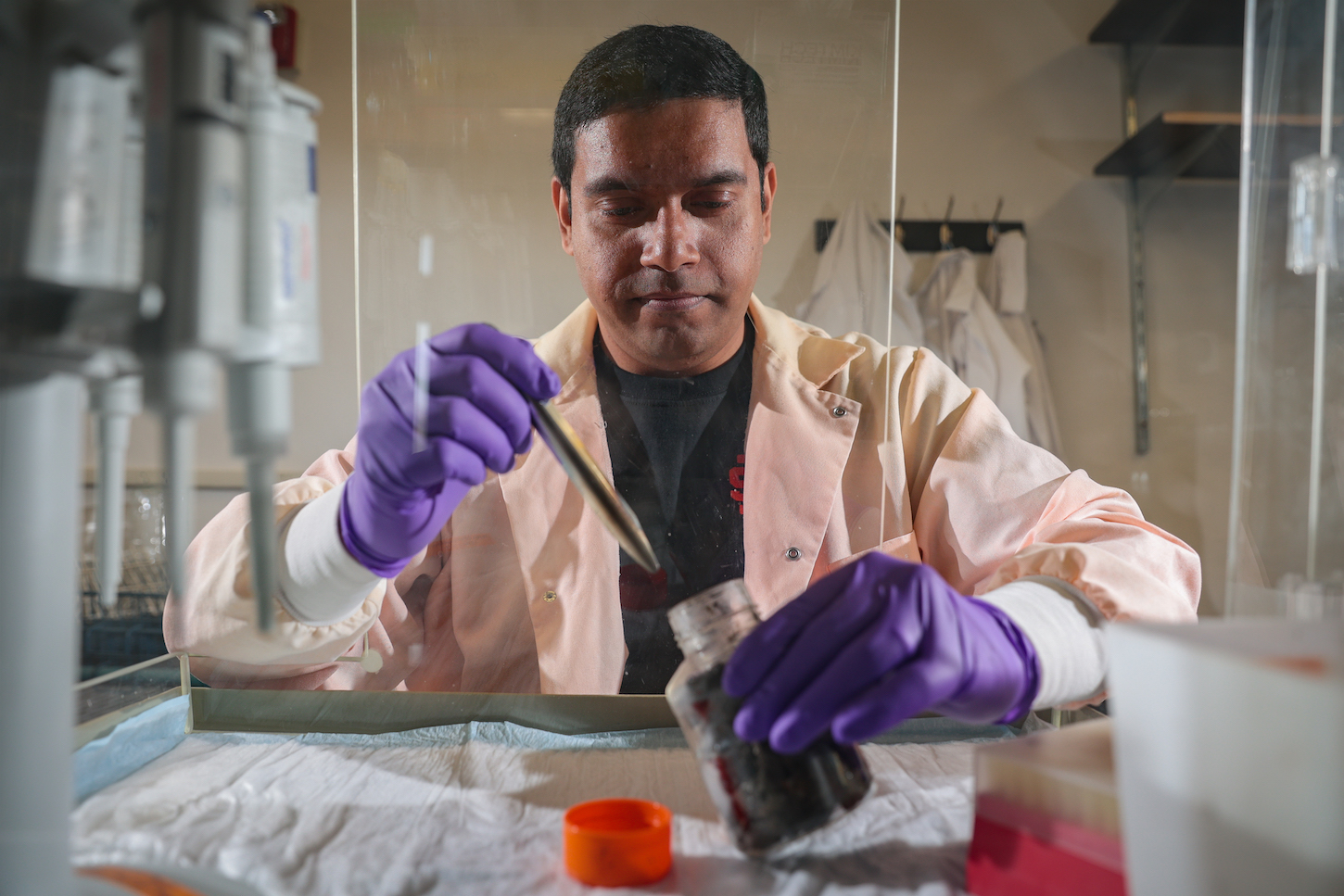

Recently, Anirban Chakraborty, assistant professor of geomicrobiology, and his collaborators’ work, “Geological processes mediate a microbial dispersal loop in the deep biosphere,” was published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s “Science Advances” journal. In the article, they detail how heat-loving bacteria circulate from thousands of feet underground up to the ocean floor and back through geological processes like hydrocarbon seepage and sediment burial.

“Our study discovered that endospores - sturdy inactive structures some bacteria make to survive harsh environments - of heat-loving bacteria living in oil reservoirs hitchhike a ride with the flowing hydrocarbons up to the seafloor,” explained Chakraborty. “The endospores lie dormant on the cold seafloor, and as fresh sediment is deposited on the ocean floor, they eventually get buried. They spring back to life again when they find new and hot oil reservoirs deep underground to call home. Essentially, the hydrocarbons seeping up and sediment burial processes act like a microbial conveyor belt carrying the microbes to the surface and back underground.”

Anirban and his co-authors, an interdisciplinary team of geologists, geochemists, and microbiologists led by Daniel Gittins and Casey Hubert of the University of Calgary, surveyed a portion of the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Nova Scotia that’s a little bigger than the state of West Virginia. The team used a wide array of tools like seabed mapping, sediment coring, hydrocarbon testing, microbial culturing, and DNA sequencing in this study.

“There is a lot to still learn about the strategies employed by microbes for thriving in such extreme environments,” said Chakraborty. “Knowing how microbial life persists in deep marine sediments can provide clues about what life may look like on other planets.”

Categories: