Blue whale meets harsh death, but will live on forever digitally

October 14, 2020

Idaho Museum of Natural History teams with Noyo Science Center on NSF project

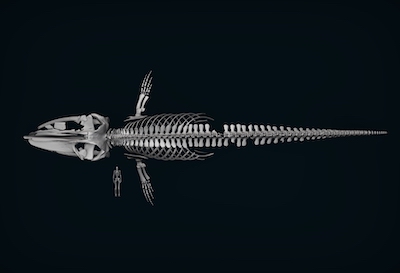

FORT BRAGG, California – The blue whale was an impressive animal measuring 25 meters, about 73 feet long, when her life ended tragically in 2009. However, she will live on forever virtually through the efforts of the Noyo Center for Marine Science in Fort Bragg, California, and the Idaho Museum of Natural History’s virtualization laboratory, which were funded by a National Science Foundation grant to digitally scan the whale’s skeleton.

This is only the second blue whale skeleton in the world to be scanned and it is the first of a North American animal. It is also the highest resolution scan of a blue whale in the world.

This is only the second blue whale skeleton in the world to be scanned and it is the first of a North American animal. It is also the highest resolution scan of a blue whale in the world.

“She was tragically hit when she surfaced underneath a boat and then the back propeller of the boat sliced her spinal cord,” said Sheila Semans executive director of the Noyo Center.

The giant animal – blue whales are the largest animal to have ever lived on the Earth – crashed ashore just south Fort Bragg near its botanical gardens “into a tiny, little finger cove with 40-foot cliffs on either side.” The whale’s skeleton and skull sustained damage as it was tossed around in the small cove, but then 200 community volunteers proceeded to salvage the whale’s bones.

“We actually had to enlist some of the heavy machine operators around here to help us pull the bones up the cliff,” Semans said. “You couldn’t carry much up out off the beach. It was quite a feat.”

Over the week-long flensing event, volunteers deboned the whale and all the meat and blubber were composted. The bones were buried for four years, then the clean bones were taken out of the ground and stored. Eventually, the Noyo Center wants to display the entire skeleton in a new facility in Fort Bragg.

Over the week-long flensing event, volunteers deboned the whale and all the meat and blubber were composted. The bones were buried for four years, then the clean bones were taken out of the ground and stored. Eventually, the Noyo Center wants to display the entire skeleton in a new facility in Fort Bragg.

But, thanks to the efforts of the Idaho Virtualization Laboratory (IVL) on the campus of Idaho State University in Pocatello, Idaho, the skeleton of that blue whale is already available to view online, due to the efforts of IVL Manager Jesse Pruitt, and Tech Specialist Tim Gomes, who scanned the blue whale bones on a 15-day trip in the summer of 2019, in which they also found the time to scan the world’s largest articulated orca skeleton on display at Noyo’s Discovery Center and a gray whale skeleton mounted for display at MacKerricher State Park. Those scans have now been uploaded to the web. Their efforts were funded by $20,000 from the National Science Foundation’s Arctic Social Sciences Program, and is part of a larger effort to digitally scan all vertebrate animals on the planet.

“It was a really massive project for us,” Pruitt said. “Before this we had scanned a humpback whale, but that is only about a third of the length of this animal. It wasn’t any more difficult than scanning anything else other than just moving the big parts around. It would be hard to top this. The only thing bigger we could scan would be a larger blue whale.”

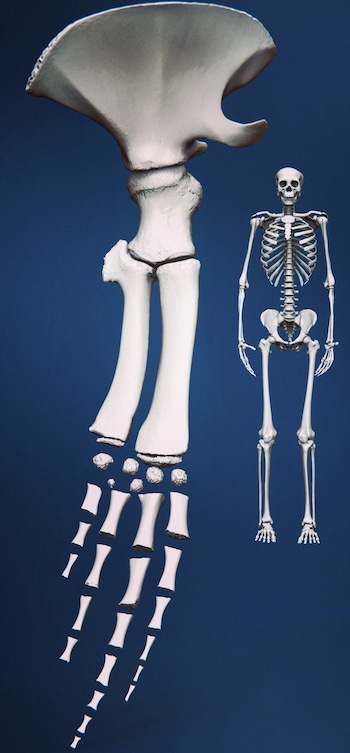

One of the larger pieces included a piece of the skull that was 8 feet wide and five feet long, which required getting a team of people with some boards and rope to move it around when it was being scanned. The mandibles, the whale’s unattached lower jaw bones, were also quite large.

“Those things are 15-feet long in their current state and it took quite an effort to move them,” Pruitt said. “They are really, really heavy, dense bones and they still have oil and grease in them from when the animal was alive.”

“Those things are 15-feet long in their current state and it took quite an effort to move them,” Pruitt said. “They are really, really heavy, dense bones and they still have oil and grease in them from when the animal was alive.”

“The goal of this and all the data that we have online now is to have it freely available to the public with as few strings attached as possible,” Pruitt said. “Anybody can come and download it for any purpose they see fit.”

The Idaho Museum of Natural History director Leif Tapanila said the timing of the project was key.

“To be able to capture the whole anatomy of the largest animal ever is pretty special. Not only are blue whales rare in collections, but to find one that is nearly complete and not stitched together for display is uncommon,” Tapanila said. “Once they are hung for people to view you can’t scan them at that point because many of the important bones surfaces are concealed. The timing to scan this one was just spot-on perfect.”

The IVL uses hand-held scanners to scan any animal that is too large to fit into computerized tomography (CT) scan machines where smaller animals are being scanned digitally.

“A big motivation for digitizing all these specimens that are in museum collections is that scientists and people in general are very interested in knowing and understanding the biodiversity of the entire planet,” Tapanila said. “Vast collections can be ‘hidden in the basements of museums’ so to speak, but if you published them online it is easy for people to access the catalog of life.”

There are practical reasons as well. Engineering and construction design firms, for example, can use these models and incorporate them into designing marine projects. In the case of the Noyo Center, these digitized models can also be used to 3D-print missing or damaged parts of its blue whale skeleton that will go up on display. “Partnerships like this with the IVL are critical in helping a small nonprofit like Noyo Center share these incredible assets with the world,” Semans said.

“So there are direct, applied reasons to do it, but of course the longer -term reason is to capture the biodiversity that exists on our planet in a digital mode that is future-proof and we can share it for all sorts of different purposes with the American public,” Tapanila said.

A scan of the whale can be viewed online at http://bit.ly/BlueWhaleScan.

Categories: