Idaho State University geologists help piece together details of Nevada’s immense Alamo crater

February 3, 2015

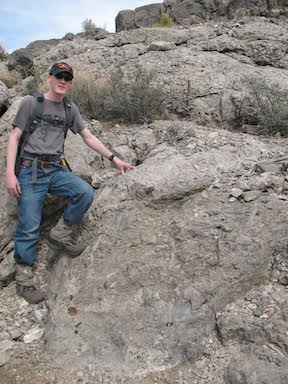

Idaho State University’s Leif Tapanila has spent more than a dozen years studying a “whopper of a hole” in Nevada, discovering more about the impact of a comet about 380 million years ago that left the Alamo crater, which is about 60 miles wide and two miles deep.

“It is one of the largest comet impact craters that has been discovered in the last while,” said Tapanila, who is the chair and associate professor of the ISU Department of Geosciences. “Even though the area has been twisted up by mountain building, it is a great spot to look at the environment and see what it was like before and after the comet hit. We get a perfect time slice of that historic event. We’ve been mapping out the extent of the crater, basically starting to piece it back together.”

The crater, located about 100 miles north of Las Vegas, was made by a ½-mile- to 3-mile-wide chunk of space debris that smashed into the Earth with a force of many nuclear blasts. Rocks the size of buildings where crumpled like soda cans, and the comet penetrated the crust of earth creating a crater, that was further enlarged when its edges collapsed, Tapanila said.

The crater, located about 100 miles north of Las Vegas, was made by a ½-mile- to 3-mile-wide chunk of space debris that smashed into the Earth with a force of many nuclear blasts. Rocks the size of buildings where crumpled like soda cans, and the comet penetrated the crust of earth creating a crater, that was further enlarged when its edges collapsed, Tapanila said.

The body that hit was likely a comet made of “frozen ice, methane and a little bit of rock mixed in” and referred to by geologists informally as a “dirty snowball.”

Piecing it back together has been a challenge, because since the Alamo comet struck many, many millennia ago, much has changed in the landscape. For one, what is now dry land was underneath water.

Piecing it back together has been a challenge, because since the Alamo comet struck many, many millennia ago, much has changed in the landscape. For one, what is now dry land was underneath water.

“The comet hit back when ocean covered Nevada,” Tapanila said. “This is one of the relatively rare impacts that has been measured of a comet that has struck ocean because it hit close to shore.”

Researchers estimate the comet hit close to the ocean shore in water 30 to 100 yards deep.

Piecing the crater together has also been a difficult task because the tectonic plates and other geological processes have pushed apart the crater over time.

“You just don’t fly over and see a giant hole in the ground,” Tapanila said. “This is one of the first projects to piece together an ancient impact site that has been pulled and twisted apart through its history. Through modern mapping techniques we were able to piece it together.”

Tapanila is a co-author on a study “Post-impact depositional environments as a proxy for crater morphology, Late Devonian Alamo impact, Nevada” that has been published this month in the journal Geosphere. The co-authors are all former ISU graduate students who have worked with Tapanila.

Comet impacts on this magnitude rarely occur, only happening every “tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands years,” but scientists still learn a lot from studying them.

Comet impacts on this magnitude rarely occur, only happening every “tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands years,” but scientists still learn a lot from studying them.

“There are still comets passing close by the Earth and our planet will get hit by them again,” Tapanila said. “Studying the Alamo crater is ancient history, but the ancient record tells us a lot about the frequency and severity of impacts and the net results of when they do happen, and that is valuable information. We can envision how a collision like this may impact the Earth today.”

Categories: