ISU researchers use spy cams to gather critical info about sage grouse

July 25, 2008

Maxwell Smart, James Bond or  Ethan Hunt and other tinsel-town spymasters have nothing in the way of tricky gadgets over Idaho State University researchers who are trying to determine which predators are eating the eggs of sage grouse.

Ethan Hunt and other tinsel-town spymasters have nothing in the way of tricky gadgets over Idaho State University researchers who are trying to determine which predators are eating the eggs of sage grouse.

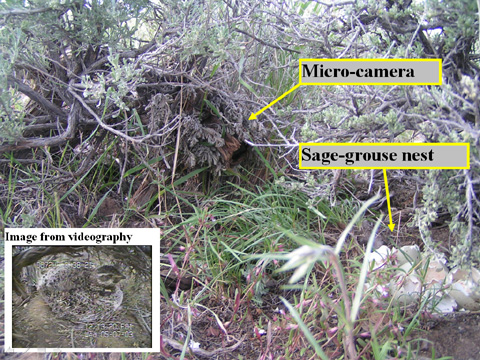

The researchers employed miniature, camouflaged infrared cameras to gather irrefutable evidence of what predators were eating sage grouse eggs, and to study a variety of sage grouse nesting behaviors. One finding of their research is that ground squirrels may have been unfairly linked to the predation of sage grouse eggs in nests. In addition, ravens have turned out to be a major predator of eggs in sage grouse nests.

Sage grouse are a species of “great conservation concern in the West,” according to Delehanty, and their range, distribution and overall population have declined drastically.

These efforts by ISU researchers to better identify the reasons for sage grouse population declines could become invaluable as efforts to protect these birds continue. Land managers in Western states are collaborating in their efforts to protect and manage sage grouse populations, to keep them from potential listing as “threatened or endangered” under the Endangered Species Act.

“The camera results are fascinating,” notes David Delehanty, Ph.D., Idaho State University associate professor of biology. “This technology has been developed for security purposes, but we’re employing it for conservation. We finally get to see firsthand behaviors we’ve wanted to see for a long time.”

Delehanty and Peter S. Coates, Ph.D., believe they are the first to use the cameras in sage brush ecosystems that take continuous footage of the animals to study interactions. Coates is a former ISU graduate student and now works as a research scientist for the United States Geological Survey.

A major factor associated with sage grouse population declines, at least in some areas, is the predation of sage grouse eggs by a variety of suspected predators. The Idaho State University researchers employed high-tech cameras to document predation.

A major factor associated with sage grouse population declines, at least in some areas, is the predation of sage grouse eggs by a variety of suspected predators. The Idaho State University researchers employed high-tech cameras to document predation.

The scientists first radio-collared sage grouse and then located their nests at various sites in southern Idaho and northeast Nevada. When the nesting sites were found they mounted the cameras for around-the-clock monitoring for weeks at a time at the nests. Through the use of the cameras, the researchers may have corrected misperceptions by previous researchers, who made judgments on sage grouse egg predation based on theremains of eggs in nests, seeing various predators in the vicinity of nests and other behaviors.

Three major presumed predators of sage grouse eggs included ravens, ground squirrels and badgers. Some species of ground squirrels were suspected of being predators of eggs because of the remains of eggshells found in their scat and their occurrence near nesting sites. In addition, in eastern North America, there is definitive evidence of some species of ground squirrels preying.

Film footage shot by Delehanty and Coates, however, repeatedly shows ground squirrels unable to successfully bite through eggs in nests. The eggs are simply too large for the squirrels. The ground squirrels were, however, seen consuming leftover eggshells, a valuable source of calcium, after the actual nest predator had destroyed the eggs. Thus, previous researchers who saw shells in ground squirrel scat and ground squirrels frequenting sage grouse nests were likely drawn to making incorrect assumptions.

Film footage shot by Delehanty and Coates, however, repeatedly shows ground squirrels unable to successfully bite through eggs in nests. The eggs are simply too large for the squirrels. The ground squirrels were, however, seen consuming leftover eggshells, a valuable source of calcium, after the actual nest predator had destroyed the eggs. Thus, previous researchers who saw shells in ground squirrel scat and ground squirrels frequenting sage grouse nests were likely drawn to making incorrect assumptions.

“The thing that most surprised us is the degree to which ground squirrels were not predators and the degree that ravens were predators of sage grouse nests,” Delehanty noted. “We filmed ground squirrels coming into nests time after time, and, without exception, they couldn’t open the eggs.”

The ISU biologists have noted a dramatic increase in the predation of sage grouse by ravens. Raven numbers are increasing dramatically in the West in response to the expansion of roads, power lines, landfills and agricultural activity. Depending on the area, raven numbers are up 200-500 percent from historically numbers near sage grouse habitat.

“The more ravens you have, then more nest predation there is by ravens,” Delehanty said. “And the more human alteration of the landscape you have, the more ravens you have. We have two native species that the public values, and one’s population is drastically shrinking while the other is experiencing drastic expansion, due to the same cause, more human activity.”

Besides the predation, ravens also affect sage grouse behavior in other ways: where there are more ravens, researchers noted that nesting female sage grouse stay on their nests much longer, leaving less often. Normally, when incubating eggs, the sage grouse stay on their nests 24 hours a day, seven days a week, except for about 25 minutes near dawn and at dusk. When ravens are present, they birds stay on their nests even longer. Those few minutes away from the nest allow the female sage grouse to drink water, and forage. Less time foraging may cause “substantial physiological distress” on the sage grouse, according to Delehanty.

The researchers will continue studies on sage grouse.

“The Western states are trying to cooperate to manage sage grouse to keep them from being listed,” Delehanty said. “This is actually an example of the Endangered Species Act working well, because even the threat of a listing is enough to get the states and their agencies cooperating to address the population decline.”

Categories: