ISU Fires Up 3D Printers to Produce PPE for the Community’s COVID-19 Health Care Response

In the early stages of the response to the COVID-19 epidemic in late March, it was clear local health care providers were short of critical personal protection equipment, so the Idaho Museum of Natural History and other Idaho State University entities and partners fired up 3D printers to help meet a pressing need.

By early April ISU was starting to deliver masks, face shields and mask straps to health care providers, with the bulk of the products going to Southeastern Idaho Public Health, which distributed the PPE through its channels. Eventually, ISU handed off hundreds of PPE products.

“There was a lot of enthusiasm and willingness to help out even though at the time it was very frightening, we didn’t know the demand and didn’t know how it was going to impact Southeast Idaho,” said Leif Tapanila, museum director who coordinated ISU’s PPE effort. “There was a lot of concern about how to deal with the crisis. I thought it was really great how many people we had come together to help and a lot of groups got on board right away who had materials ready to go then and there.”

At ISU, the museum, the Oboler Library, the College of Technology and the mechanical engineering department worked on plans to produce PPE. Tapanila also coordinated with the Pocatello Marshall Public Library.

“We had to create a supply and there were a lot of conference calls at the beginning of the month in April, but we got the machines online and got the process rolling,” Tapanila said. “What I really enjoyed seeing was all these different groups from campus rallying around the need to produce more protective gear.”

ISU and its partners made several different products. The most sophisticated was what is commonly known as a Montana mask, which is similar to a N-95 mask, that is a hard, surgical mask that can be fitted with a filter.

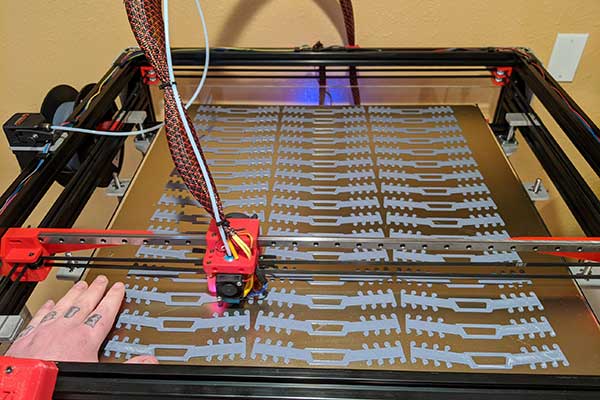

Idaho Museum of Natural History 3D printer producing plastic mask straps used to attach straps from facemasks

“It is not quite an N-95, but it is similar in the sense that it filters very, very fine particles out of the air,” Tapanila said. “So that is used by medical folks and we gave some to the police department and public safety on campus.”

The Idaho Museum of Natural History made 339 of the Montana masks, and a total of 562 were produced with the help of partners.

The second main product produced on printers were headbands that had large, plastic clear shields that covered the face, making a semi-circle around them. The museum produced 99 of them and a total of 172 were given out.

In addition, the museum made about 900 mask straps that are a simple piece of thin plastic with barbs on them. The purpose of these straps is to hook the elastic bands of a face mask around the barbs on the plastic straps, to increase the comfort of wearing a mask with an elastic strap.

“The lion’s share of the products went up to Southeastern Idaho Public Health,” Tapanila said. “They distributed them out to folks in need. We were trying to use them as the centralizing group to distribute them as was needed.”

“ISU’s creative use of this technology provided critical tools to our health care providers and first responder community, at a time when PPE was needed but in limited supply,” said Maggie Mann, SIPH director. “We truly appreciate their partnership in this response.”

Other end users for the ISU PPE products included the Portneuf Medical Center Pathology Laboratory, Portneuf Medical Center Infection Control, the Pocatello Police Department, Malad Hospital, a hospice care center and the Intermountain Medical Clinic.

The PPE 3D printing effort was suspended by the end of April and the Idaho Museum of Natural History and other partners went back to using them for other purposes.

“But it would be very easy for us to switch the mask-making effort back on if and when there is a demand to meet,” Tapanila said. “This feels like something tangible and real that we can do to help the community.”