Plastic-Eating Mushrooms

Sporadicate Partners with City of Pocatello and Idaho State University on Environmental Sustainability Initiative

Picture this: you own a banana field in Guatemala. You cover your bananas in a blue plastic material to keep bugs and other pests away from the fruit. What do you do with the plastic when you’re done with it?

Gavin Pechey, who was in Guatemala researching the textile properties of banana tree fibers, posed this question to the owner of the field he was visiting.

“The owner wasn’t proud of it, but he admitted he threw the plastic coverings in the river when he was done with them,” said Pechey. “This was likely happening at many of the other banana fields as well. Thousands of plastic coverings were being thrown into the river every year. I thought ‘there has to be another way.’”

This was just one example of a worldwide problem – plastic waste isn’t going anywhere.

“A lot of people don’t realize how long plastic lasts,” said Pechey. “You could wake up in 500 years and that plastic container you threw away yesterday would still be there.”

Though there are recycling programs worldwide, only a small percentage of these materials can actually be recycled using current methods - around 9 percent.

So, what’s the solution? Could it be… mushrooms?

Only 9% of plastics can be recycled

That’s what Pechey and his team at Sporadicate are trying to find out. Pechey’s experience in Guatemala was the catalyst for a man who already had a passion for environmental sustainability and business development.

Through initial experimentation, Pechey and a mycologist determined there are several species of mycelium (the vegetative, root-like structure of fungus) that have the ability to break down plastics and remove harmful pollutants. They also realized this solution could be broadly scaled.

Jump to 2023, and the Sporadicate team was assembled to develop the technology and processes needed to bring plastic pollution solutions to market. With everything needed for the first test site set, their eyes turned to Pocatello, Idaho.

“Pocatello was an ideal test site because of the amount of recycling the city is currently processing monthly - around seven tons,” said Pechey. “We were also met with great support from the city from the very beginning.”

What does being a ‘test site’ entail? Sporadicate will work within a three to twenty acre to-be-determined plot of land within the city. The process starts with a hole in the ground.

Plastic that has been washed, cut into strips and soaked in a substrate to support mycelium growth is placed in the hole and covered. Over time, the mycelium of the fungi grows and spreads throughout the plastic waste, secreting enzymes that break down the plastic polymers into simpler compounds. As mycelium grows, it decomposes the plastic.

Part of Sporadicate’s agreement with Pocatello included working with Idaho State University. They were directed to the ISU Office of Research to talk to Vice President of Research and Economic Development, Martin Blair.

“I got a call from the CFO or the City of Pocatello, Eugene Hill, who’s also an entrepreneurial-minded person,” said Blair. “He and other city employees had been in contact with Sporadicate and saw the potential that was there. With one of ISU’s main research focuses being sustainability, I saw the potential, too.”

“We could create a hybrid mushroom that would do well breaking down several types of plastics.”

Since their initial connection, Blair has connected Pechey and his team to several other units across the University campus, including the College of Business Commercialization Center for grant writing and industry research, and the College of Science and Engineering for mushroom species testing.

“I knew if I got the right people together, they would know where to take this opportunity,” said Blair.

“The Commercialization Center is all about helping to bring innovative ideas like this to reality,” said Clinical Professor of Management and Director of Bengal Solutions Nikole Layton. “We were excited to bring College of Business faculty, as well as students from Bengal Solutions (a graduate student led consulting business), in to assist with grant writing, marketing and industry research efforts. At the end of the project, we were able to present Sporadicate with a full commercialization plan.”

“My team worked on a market analysis that included things like a SWOT analysis - recognizing and discovering strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to their business, as well as the industry in general,” said Master of Business Administration student and Bengal Solutions team member Taylor Killpack. “It’s great to get a real-world experience like this helping businesses grow and enter the market.”

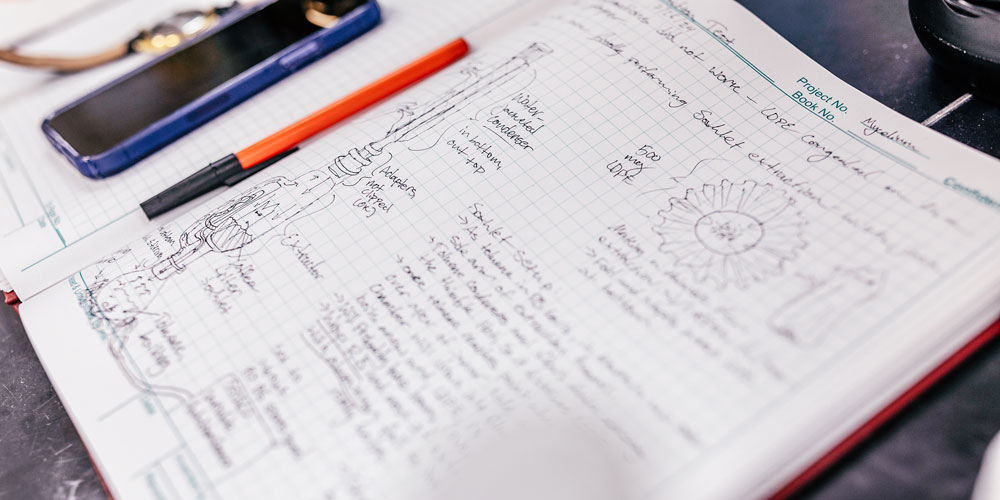

Mushroom testing is taking place inside ISU’s state of the art research facility, the Eames Complex. Pechey is working alongside Senior Lecturer in Biology Education Dr. Jack Shurley, Chemistry Professor, Dr. Joshua Pak and biochemistry student Will Hine.

“We want to see which mycelia do well with what types of plastic and begin to understand why,” said Pak. “With this information, we could potentially create a hybrid mushroom that would do well breaking down several types of plastic.”

Pak also noted a hybrid could potentially reduce the time it takes to begin breaking down the plastics. Right now, the process takes around 120 days. Their goal is to reduce this by half. “These [hybrids] would be the most [ideal] for real-world applications,” said Pak.

“The mixture of chemistry and microbiology in this project is really cool,” said Hine, a transfer student from the College of Southern Idaho who gained the opportunity to work on the project through the SPARK a FIRE Scholarship. “This could be a natural remedy for the plastic waste problem, which should be a high priority for people.”

“This project has been a great example of people from across the University coming together to make things happen,” said Blair. “We’ve had the opportunity to engage with the public on the research that’s happening at ISU, work towards solving real problems and begin to engage students from freshman to Ph.D.”

So, what does the future look like for Sporadicate? This is really just the beginning. Sporadicate plans to begin working with more students at ISU and using land Pocatello provides.

“We’re excited to continue working with the City of Pocatello and ISU,” said Pechey. “Our goal is to eventually be able to process twenty tons of plastic a week, expanding into other areas of Bannock County and continuing west.”